This Week’s Must Read: My Story: 50 Memories from Fifty Years of Service

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum’s eagerly-awaited memoirs chart the United Arab Emirates’ meteoric growth into a global superpower and offer a rare glimpse of the man at the heart of power and politics in the Middle East, finds Timothy Arden.

Competition is a word Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum uses a lot.

The Prime Minister and Vice President of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) believes it’s an essential trait of human nature, driving people to become stronger and to achieve more.

“Compete with yourself and others,” he urges readers in My Story: 50 Memories from Fifty Years of Service, his long-awaited memoirs published to coincide with half a century at the heart of power and politics in the Middle East. “Compete with your goals to achieve more ambitious ones,” he adds. “Compete with your past to build a better future.”

This characteristic was clearly at play on December 6, 2017 when Sheikh Mohammed, who is also the Ruler of the Emirate of Dubai, announced plans to send the first UAE astronauts to the International Space Station. The project would, he knew, send an inspirational message to the people of this relatively young nation: Nothing is impossible. It was fitting – and surely no coincidence - that such an audacious objective was shared with the world, and with millions of his personal followers, on Twitter.

My Story comprises a fascinating collection of anecdotes and reminiscences to mark the Sheikh’s fifty years in public service, stretching back to his first official appointment as Dubai’s Minister of Defence in 1968. From its pages, packed with many never-before-told revelations about the Sheikh’s dealings with Middle Eastern and world leaders, emerge an enlightening picture of a man whose approach to life and to politics blends the progressive with the traditional. His values are, we learn, shaped by an affinity and deep-rooted respect for his country’s rich history but also by a forward-thinking commitment to contemporary values.

As My Story makes clear, the secret of this remarkable and unprecedented transformation, can be credited to the visionary leadership of founding fathers including the Ruler, his father, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, and its first President, popularly known as the “Father of the Nation”, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan. They have all been guided by an unflinching will to succeed and shared view of competition as a driver for positive, and lasting, change.

It’s perhaps in relation to commerce and trade where the Sheikh refers to the concept of competition most frequently. Companies, he believes, are most likely to succeed when they compete in an open environment. It’s a fear of competition, rather than the existence of it, that all too often destroys them.

It was this conviction that drove him to transform Dubai from a small and bustling trading port into what it is today: a multi-billion dollar city that welcomes 16 million visitors annually from around the world. This he achieved in just five decades after being appointed as its Head of Police and Public Security in 1968.

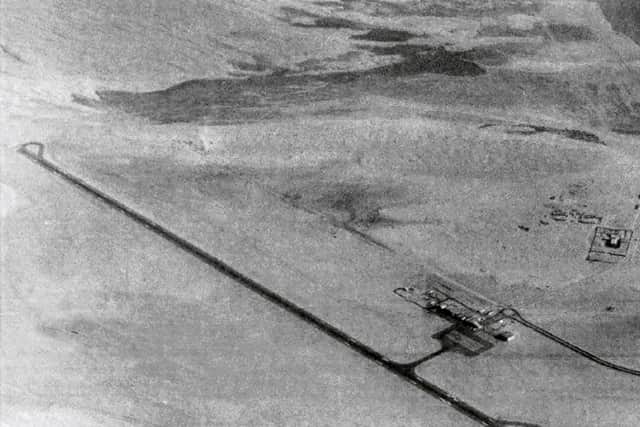

In one of many revealing anecdotes and reminiscences—there are 50 in the book, one for each year of service—Sheikh Mohammed recalls the moment when he first realised that Dubai had the potential to become a global landmark and economic hub. He was a child on his first visit to Britain, standing “bewildered” at Heathrow Airport, watching the commotion and dreaming Dubai might one day have its own airport. From that instant, he firmly believed that the future lay in making it a global destination.

It has remained his focus - a personal mission, even - ever since, despite intense opposition in the early years. His vision was, for example, roundly derided at a meeting of the Gulf Cooperation Council in the early 1980s. Who would possibly visit Dubai?

“I knew that we were sitting on tourist gold: sun, sea and white sands,” Sheikh Mohammed tells the naysayers. “Build it and they will come”. He later embarked on creating state-of-the-art visitor and entertainment facilities, huge malls and vast infrastructure projects.

Dubai International Airport is now bigger than Heathrow.

Whether that competitive spirit is innate or whether it was acquired later in life is unclear.

What is apparent, however, is that it permeates every aspect of his life, including the pursuit that has made him familiar to many the UK – horse racing.

As founder of the Godolphin and Darley racing operations, one of his biggest wins was in the prestigious Dubai World Cup in 2000 when Dubai Millennium, ridden by Frankie Dettori, stormed home in first place “attacking the finish line like a hurricane” and notching up a new track record.

“It was a dream coming true before my very eyes,” writes Sheikh Mohammed, recalling how he’d headed to the stables on the eve of the race to spend a few quiet moments on his own with his “beloved” colt, giving him quiet encouragement.

It’s a touching scene and one that echoes another, some decades earlier, when, on the eve of his debut race riding his own first horse (Sawda Umm Halaj, meaning ‘The black one with the earring’), he’d walked a 2km racetrack on Jumeirah Beach with the mare, telling her of his hopes for the day ahead. The Sheikh didn’t win – he came in second – but reveals the experience taught him a valuable lesson: “[That] achievements are never accomplished without hard work”.

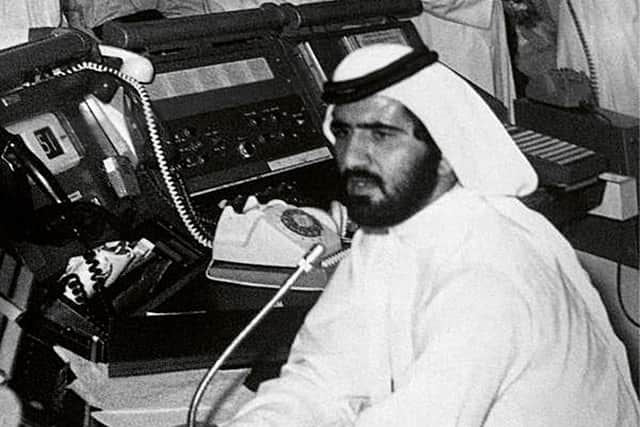

When the UAE was established as a federation in December 1971, his indefatigable work ethic was tested, perhaps to the limit. At the age of just 22, he set about building a defence capability, unifying the forces of the seven Emirates which constitute the UAE under one federal umbrella. Deemed the top priority for the new government’s initial five-year term in a bid to deter foreign threats and ensure internal stability, the project frequently involved nineteen-hour days. The Sheikh devised a strategy and command structure, acquired equipment and technology, and trained alongside his forces. He was the youngest Minister in the world at the time.

It was his toughest-ever challenge and one that was compounded by a series of events that required his personal and immediate attention: armed conflicts between tribes, an attempted coup d'état involving the murder of Sharjah’s ruler, and a hijacking by the Japanese Red Army in 1973 which saw a plane land in Dubai with the terrorists threatening to kill everybody on board. Sheikh Mohammed led the three-day negotiations, offering to refuel the plane but refusing to give the hijackers asylum in the UAE (they eventually headed for Libya, where all of the passengers and the flight attendants were released, but the plane was blown-up).

The incident gave him an early insight into the mindset of terrorists and shaped his loathing of their philosophy. “For many decades our region has suffered from this utterly self-defeating and oppressive thinking: that terror is a solution to injustice,” he writes. “Countries have lost thousands – even hundreds of thousands – of people to this philosophy of hatred. Many communities around the globe have lost decades of growth and development because of a terrorist ideology that begins with a just cause and ends with the utterly unjustified slaughter of innocent lives.”

While his competitive nature fuelled his aspirations for the country’s defence force, he was acutely aware of the need to balance military spending with other priorities, such as developmental progress. “No country can consider its military strength more important than the welfare and comfort of its people, too,” he explains.

Today, he points out, countries such as North Korea may have some of the largest military forces in the world, but their people are poor – sometimes to the point of starvation. Conversely, countries such as Japan may not have big armies, but the power of their economies means they stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the greatest of nations.

We learn that Sheikh Mohammed’s bid to develop world-class Armed Forces capable of “defending the homeland” was conditioned by the training he’d already acquired at Mons Officer Cadet School in Aldershot, Hampshire, along with a spell in Cambridge, where his father had sent him to learn English – conscious that an ability to speak the language would become an increasingly important asset as the world became more globalised.

His father, Rashid bin Saeed, had long since held the vision of creating a federation of the seven emirates (originally together with Qatar and Bahrain) – a dream that stepped up a gear between 1969 and 1971 as the would-be partners negotiated such issues as the distribution of power and budgets. The young Sheikh Mohammed had a ringside seat as the plan evolved, accompanying his father to meetings and on trips. These personal experiences and recollections offer a candid, intimate insight into some of the Middle East’s most important historic moments.

He recalls, for example, meeting the British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, in 1969. Tensions were running high. While the British had announced their intention to withdraw from the Gulf within three years, his father had concerns they would maintain “desires and ambitions” for the region so was pushing hard for total independence.

Sheikh Mohammed recounts his amusement at how the conversation ping-ponged between Wilson’s broad Yorkshire dialect and his father’s Bedouin accent. Watching the two leaders smoke as they talked, he learnt a valuable lesson in the art of politics. In typical British fashion, Wilson had observed how much bigger his pipe was than his visitor’s. Sheikh Rashid had simply smiled and pointed out how strong and powerful his tobacco was. It was, Sheikh Mohammed realised even at that tender age, a display of the subtle language of politicians, conveying unspoken messages. Wilson’s words may have hinted at the UK’s size and power, but his father’s considered reply conveyed the importance of not underestimating his determination.

The talks concluded on a positive note and, despite initial noises from the new Edward Heath government in 1970 that the Conservatives wished British forces to remain in the Gulf, Heath later announced the UK would indeed withdraw.

As a young man, Sheikh Mohammed’s father had himself accompanied his own father, Sheikh Saeed bin Maktoum, on such trips. Sheikh Saeed had come to power in Dubai in 1912 and in many ways was the man who kickstarted its journey towards becoming a global city.

Although Dubai’s roots as an Emirate date back to the early 19th -Century, Sheikh Saeed adopted a pioneering free-trade policy, developing its eponymous capital as a significant commercial hub and ensuring “the heart of a modern city began to beat” (pearls were the largest trade sector in the region until the market for them collapsed in the 1930s).

Sheikh Mohammed identifies 1979 as a pivotal year, with the launch of three huge projects – Jebel Ali Port, a vast aluminium smelting operation, and the Dubai World Trade Centre which today draws more than three million business people annually to about 500 events.

His father died in 1990 and the presence of so many Europeans, Asians, Africans and Americans among the mourners was, he writes, testimony to his father’s vision of creating a “cosmopolitan city, free from any form of discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, colour or religion”.

The lessons in diplomacy that Sheikh Mohammed learnt at his father’s side would prove invaluable in later life when dealing with other world leaders. He’s a strong proponent of maintaining small lines of communication during political crises – an approach that was evident when dealing with Saddam Hussein.

He’d dubbed Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait “an outrage”, severing links with its leader and assisting the Desert Storm coalition, comprising almost one million international troops. Emirati forces later had the “honour” of being the first to enter Kuwait to liberate the country. But fast-forward to 2003 and he was less enthusiastic about the prospect of another American intervention in the Middle East. Unconvinced that Saddam Hussein owned weapons of mass destruction and fearing the consequences, he attempted to persuade US President George W Bush not to invade Iraq.

Sheikh Mohammed visited the Iraqi leader in person – a tense meeting at which his host refused to sit in the same place for any length of time, seemingly terrified of being shot by an assassin. In a bid to avoid the bloodshed, Sheikh Mohammed offered him a home in Dubai if he stood down, but the conflict went ahead, resulting in many thousands dead and wounded on both sides, decades of lost development and groups emerging from the ravaged state that would go on to terrorise the world. “As history has taught us time and time again,” Sheikh Mohammed writes, “there are no winners in war.”

Another controversial figure with whom he had dealings was the Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi, who, following the American-led war with Iraq, had announced he was to relinquish his nuclear programme and professed a desire to build a Dubai-style city in Libya to act as Africa’s capital.

Sheikh Mohammed later cut ties with Gaddafi, suggesting the whole endeavour was “shrouded in clouds of corruption and that we were setting ourselves up to be used merely as collateral in Gaddafi’s propaganda schemes”. Gaddafi, he concluded, wished for the appearance of change but did not want true transformation.

“Change cannot happen with the scale of corruption we witnessed during our visits to Libya,” he writes. “Change needs real achievements and hard work, not simply empty speeches.”

A government’s job, he is convinced, is merely to create an enabling environment – the people will do the rest. Governments, he observes, are like traffic police standing in the middle of a busy intersection. Their task is not to stop everyone moving, except their own family and friends. Their role is to facilitate the movement of all the people, so they can collectively build their futures and their nations. “Unfortunately, our regions suffer from an excess of failed traffic policemen.”

An acclaimed poet in the Arabic Nabati style, Sheikh Mohammed’s fluent writing blends small, personal observations with insights into world affairs: recollections of his late mother, Latifa (the daughter of a one-time ruler of Abu Dhabi); of learning to hunt; and how he learnt the ways of the desert with its “constantly changing moods” are particularly touching.

الامارات-شخصياتسمو الشيخ محمد بن راشد ال مكتوم ولي عهد دبي وزير الدفاع

Ditto his reflections on role models such as Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, his “second father, teacher and mentor” and a man who, as ruler of Abu Dhabi, was instrumental in transforming the dream of a Union into a reality. It was in 1968, after Mohammed had been summoned back from Cambridge for a meeting “away from prying eyes” in the desert that his father and Sheikh Zayed shaped history: reaching a point of no return in the formation of the UAE.

The UAE is, he believes, an exception to contemporary history as the “only viable Arab country conceived by genuine union, rather than arbitrary lines drawn on a map… the only country that was built by Arab leaders through agreement rather than force; the only country that has shown how successful the outcome can be when Arabs agree and work together to build a common future for their people”.

Its openness, tolerance, prosperity and adoption of a private sector mindset in government is a model he’s always hoped would become adopted across the Arab world.

Appropriate, then, that the final chapter of this illuminating autobiography lists what he considers to be the principles of sound government, under the heading ‘10 Rules for Leadership”. Fitting, too, that this closing chapter returns to one of his favourite themes: competition. Alongside such mantras as serving the people and focusing on the work rather than titles or position, he concludes: “Competition is a way of life in government, without it, motivation will subside, enthusiasm will diminish, and the flames of determination will die out.

“My goal,” he goes on, “is always to be in first place, and I always strive for this – even when I’m not aware I’m doing so.”

It is precisely this sentiment, this irrepressible sense of competition, which will propel UAE astronauts into space and launch an exciting new chapter in the history of this ambitious, outward-looking Islamic nation.

As Sheikh Mohammed says: “Setting one’s sights on the horizon is all very well, but it is by looking beyond it that we humans fully engage our imagination to inspire true achievements.”

My Story: 50 Memories from Fifty Years of Service (Explorer Group Ltd) by Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum is out now on Amazon UK, priced £7.99 in paperback and £6.73 as a Kindle eBook.

PHOTO CREDIT: All pictures copyright Explorer Publishing 2019